Home » Exhibit

This digital exhibition celebrates the 50th Anniversary of John Jay College of Criminal Justice. From its evolution as a small school serving New York’s uniformed services, John Jay has grown to an internationally renowned liberal arts university offering a wide range of undergraduate and graduate degree programs. The College not only changed in response to historical developments both in New York City and the world, it has shaped these developments by contributing to public policy debates in such areas as criminology, penology, human rights, and ethics.

Walk through John Jay's history! Images and artifacts from John Jay’s history are on display in Haaren Hall from August 2014 through May 2015.

Browse other events celebrating John Jay at 50 »

Skip to section:

As an institution, John Jay grew out of the social turmoil of the 1960s. Issues surrounding the Vietnam War, Civil Rights, and rises in crime cast a critical eye on the police. Within the zeitgeist of the period, an idea emerged that police should be educated to better deal with the social and political issues of the time period. Running concurrent to this idea of police education was another theme: the increased specialization of police work. The necessity of a separate institution where both of these needs could be addressed was the foundation of John Jay.

Although officially opened in 1965, the College of Police Science, and the idea of educating police, finds its roots a decade earlier. The college developed from programs begun in the 1950s in two other city colleges. In 1953, Brooklyn College initiated a program in its Division of Vocational Studies leading to an A.S. degree in Police Science. And in 1954, the Board of Higher Education approved the founding of the Police Science Program at the Baruch School, to begin a year later in September 1955. The Baruch program proved reasonably successful with enrollment increasing from about 600 police officers enrolled in 1957 to 1,204 by 1964. Cramped classrooms and deteriorating buildings, however, stifled the program. Additionally, pressure was building both in New York City and nationally to expand police education.

In 1961, the city’s four senior colleges and four community colleges were united as the City University of New York. Initial reports recommended shortening the program and moving it to the Borough of Manhattan Community College. This proposal ran counter to the growing national movement to expand police education to a four-year degree. It also ran counter to a small but influential group within the New York City Police Department who were intent on upgrading and professionalizing the force. Mayor Wagner was soon approached by Michael Murphy, Police Commissioner; Patrick V. Murphy, Commander of the Police Academy; and Anna Kriss, Commissioner of Corrections, to create an entirely new CUNY police college. The idea gained traction. While the municipal colleges were producing plenty of teachers, they were neglecting entry-level professional jobs that were important to many students. The idea of the proposed police college was to fill this gap in the CUNY system. And despite some fears that the college would be controlled by the NYPD, the proposal for the new college was approved by the Board of Higher Education on June 15, 1964. Throughout the process the Board, as well as the NYPD, were committed to creating a liberal arts college that would provide police with the best education possible. Donald Riddle, then a professor at Rutgers University, was selected to be Dean of the College of Police Science, renamed in 1967 to John Jay College of Criminal Justice. In an address to the Police Academy later in 1964, Riddle set forth three basic goals that the college has focused on ever since: (1) to educate police and other law enforcement personnel, (2) to define and develop the fields of police science and criminal justice into coherent and recognized academic disciplines, and (3) to provide a strong liberal arts curriculum for its students.

This new approach developed the goal of police education. Not only was the goal to professionalize law enforcement across the nation, but it was also to see the field of criminal justice, the courts, police, probation and parole as all interconnected parts of one larger system. The college opened in 1965 with only a thousand students and one major. Throughout its growth, the college’s community has since prided itself on being an institution of higher education where the notion of justice is still a central issue.

1964 Mayor Wagner approves the creation of a new four-year police college to provide “sound full scale academic training for” police officers.

1965 John Jay College officially opens. Dean of Faculty Donald Riddle explains that its goal is to “contribute to the development of men as thinking, critical, creative beings.”

1966 John Jay puts on its first performance of a play, “The Trial,” based on Kafka’s novel. Directed by Ben Termine, it ran May 20th and 21st. “Hell of a precedent,” former police Chief Mike Murphy says.

1966 John Jay’s first class of 118 students graduate. “Most of them were in their 40’s and graying and more accustomed to wear blue and pack a .38,” according to New York News.

1966 The first civilian high school graduates attend John Jay.

1967 The College of Police Science is officially renamed John Jay College of Criminal Justice in an announcement by President Reisman on December 19.

1967 The college announces the formation of a forensic science program to “train the future police laboratory technicians who will produce the physical evidence required by the average policeman to obtain convictions.” The announcement comes only a day after the National Crime Commission’s call for expanded research programs.

1969 As a result of the Law Enforcement Administration Act, John Jay receives a $200,700 federal grant to pay for 800 police officers’ tuition, the highest such award given to any university in the country.

1969 Lloyd G. Sealy, former assistant inspector of the NYPD, becomes associate professor at John Jay College after 28 years on the force.

Open Admissions: “a guaranteed place at CUNY for any New York City high school graduate, regardless of test scores, grades, or any traditional criteria” Source »

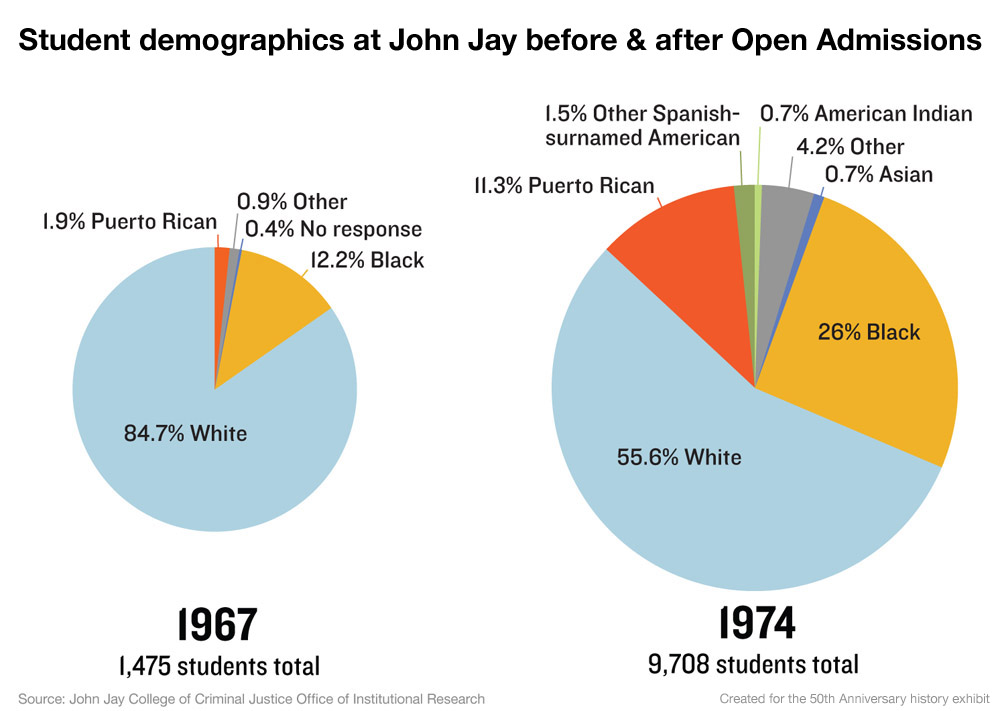

Like the expansion of police education in the 1960s, Open Admissions, implemented in the fall of 1970, came out of the storm of conflict and crisis that swept over New York at the time. Providing a place in the university for every high school graduate who desired to attend college profoundly affected all the campuses, but at John Jay it unleashed a hurricane of change that transformed the college. The size of the faculty doubled in the first year, doubled again in 1971, and grew by another 25% in 1972. The number of undergraduates grew from 2,600 (one out of five of whom were “civilians”); to 6,700 in 1972 (over half were civilians); and finally, over 8,600 students in 1973, when enrollment began to level off. Suddenly gone was the small institution devoted to primarily to in-service students with classes in the Police Academy. What emerged was a medium-sized, multi-purpose college with rented space in two office buildings in downtown, commercial Manhattan.

The old faculty was in a state of shock. The sense of community that had developed was transformed, if not disrupted, by dozens of new faculty members who were unfamiliar with what John Jay had been for the previous five years. The new faculty was predominantly young, inexperienced teachers excited about coming to John Jay. Many had been involved in the social protest movements of the 1960s, demonstrating on college campuses to promote racial integration and protest the war in Vietnam. These new faculty members, many of whom chose to teach at John Jay because of its unique mix of students, brought enormous energy and enthusiasm to the Open Admissions effort.

As a program, Open Admissions grew out of a variety of forces that shaped its structure and program. Originally conceived in the City University Master Plan of 1968, the program was not due to start until 1975. The plan was to create a three-tier system with the top third of the city’s high school graduates attending the senior colleges, the middle third guaranteed admission to the community colleges, and the bottom third going to “Educational Skills Centers” that were as yet to be developed.

The original three-tier plan was rudely disrupted, however, when, in the spring of 1969, students at City College and then at other university campuses pushed for faster change: they demonstrated, occupied buildings, and closed campuses, all to demand equal access to education for black and Latino students. In response to the activists, the Board of Higher Education announced that a modified Open Admissions plan would begin in the fall of 1970, five years ahead of schedule. As a college, John Jay was uniquely suited to this effort because of its history as an open admissions college for police, a college where Professor Ira Bloomgarden commented that already existed “the absence of selective admission standards, the absence of artificial distinctions between various classes of students, and a reasonable, flexible time schedule for the completion of studies.” This background gave John Jay a head start in responding to the changes.

For all its preparation, John Jay was caught unprepared by the challenges of Open Admissions. Everyone at the school underestimated the lack of academic readiness of the new students. No one anticipated how poorly New York City’s high schools had served their students. The radical change in the make up of the student body did little to help. For the first time, over half of the freshman class was made up of non-police students; many, perhaps most, of these students had not even expressed an interest in criminal justice as a career. The increase of minority students led to some tension between the older, predominantly white police officers. Additionally, the background of these students, usually from working-class families, meant that professors of middle- and upper-class upbringing were unable to connect with their students on a meaningful level. Only 37.2% of the class of 1970 graduated — a sign of these difficulties.

Not all was gloom, however, as the college saw an explosive growth in its majors. Out of 25 offered in 1975, 13 had been introduced between 1972–75. And despite the low averages of the incoming students, many of the professors found them to be just as motivated in obtaining success.

The quickly decreasing availability of physical space, coupled with debates over the college’s mission in the Open Admission years and the increasing budget crises of the 1970s, meant that whatever victories the college experienced were small. It was difficult to do justice to the job of educating the new Open Admissions students, but it cannot be said that John Jay did not give its fullest and most complete effort.

1970 In the midst of massive student demonstrations at campuses across the country, over 14 schools across the nation officially closed in the spring. John Jay students vote for the college to remain open by a slim margin of 865 to 791.

1971–1975 over 13 majors are established at John Jay, running the gamut from Arts and Language to Mathematics.

1970 J. Edgar Hoover forces 15 FBI agents to drop out of John Jay after Professor of Sociology Abraham Blumberg criticized the organization and Hoover himself. Jack Shaw, an FBI student whose Master’s Thesis was somewhat critical of the organization, is reassigned to Butte, Montana. Shaw resigns and sues the FBI for back pay. He eventually gets $13,000 from a settlement.

1971 John Jay offers graduate fellowships to minority groups interested in government careers. Fellowships are made possible by a Ford Foundation grant to National Association of Schools and Public Affairs and Administration (NASPAA).

1972 The National Endowment for the Humanities gives John Jay $476,887 for an Experimental Humanities Program at the school.

1973 John Jay College institutes a new experimental program, offering college courses for police officers at Police Precinct 50 in Kingsbridge Terrace in the Bronx. Four courses are offered: literature, American government, cultural anthropology, and police organization and administration. At this time, the college is also offering courses to inmates who are in jail at Rikers Island.

1975 Gerald Lynch, psychology professor and Vice President at John Jay, is named acting president of the college, after previous president Don Riddle resigned to become Chancellor of the University of Illinois, Chicago Circle.

In the fall of 1970, in the midst of the FBI controversy, John Jay was experiencing the other profound shock of the beginning of Open Admissions. The program presented a number of challenges for John Jay. Socially, the student body changed dramatically. For the first time, over half of the freshman class was made up of non-police students; many, perhaps most, of these students had not even expressed interest in criminal justice as a career. In addition, these students were much younger, and a much higher percentage of them—about one-third—were African-American and Puerto Rican. The rest of the new students were ethnic whites, especially, Irish, Italian, and Jewish. Most of the new students, both black and white, were substantially less affluent than the police students. Despite their similar backgrounds, the police were earning higher salaries than the parents of the new students. The Open Admissions students were also poorer than the average college students entering schools across the nation: 45% of John Jay’s first Open Admissions class came from working-class and poverty-stricken neighborhoods, as compared to 15% nationally. The new students were also overwhelmingly first-generation college students. Only 19% were not.

The tremendous growth occasioned by Open Admissions led to the expansion of the liberal arts during this period. Because most of the new faculty was in traditional liberal arts areas, and because the focus was now on the “new” Open Admissions students, the liberal arts could expand and develop as never before.

Arthur Pfeffer summed up the era well: “Those were days of great opportunity and enthusiasm, but also of great confusion and insecurity.” The college grew tremendously during this period and experienced an extraordinary vibrancy, excitement, and diversity. John Jay tried to fulfill the democratic promises of Open Admissions, and it certainly achieved some great successes, educating many students who would never have had a chance before 1970. It also experienced lively debate about the differing conceptions of John Jay’s future and role. But as budget cuts continued year after year, and as the city sank further and further into the abyss, faculty and students began to feel that they were the butts of some cruel joke. It was difficult to embrace the challenges of Open Admissions, and it was almost impossible to become at the same time an elite college of criminal justice. Increasingly, people worried only about survival.

Everybody in New York knew that with annual budget cuts and “crisis” in the 1970s, the city’s fiscal standing was not good. No one, however, understood just how desperate the situation had become.

On Monday morning, February 23, 1976, John Jay’s faculty and students awoke to read this New York Times headline: “City University Chancellor Urges Closing of Three Colleges.” After months of rumors and speculation, they did not have to read far into the article—it was on the third line—to learn that Chancellor Robert Kibbee recommended the John Jay, Richmond, and Hostos be closed. The worst had happened. The college was going to close in September.

Under Kibbee’s plan, John Jay’s criminal justice program was to move to Baruch College, and the remaining students were to be enrolled in standard liberal arts and science programs throughout the system. The proposal argued that John Jay was too expensive to maintain because of the high cost of its rental space and its many counselors and tutors. In effect, after giving the college the highest percentage of poorly-prepared students, the chancellor’s plan criticized the college for using so many counselors and tutors in its attempt to make Open Admissions a success.

Upon reading the outline of the plan in the newspapers, the faculty and staff felt that they had been dealt a mortal blow—it threatened their livelihood and spelled the end of John Jay, a college that many of them had helped build from scratch. President Lynch mobilized the faculty, staff, and students to action. He argued that everyone knew someone in politics, the media, or other influential areas, and they needed to go into their communities, speak to their relatives, colleagues, clergy, and local politicians, and urge them to write, call, and speak out to prevent the closing of John Jay. Lynch’s team, Acting Vice President Richard Ward and John Collins, working with the faculty and outside consultants, started to devise a strategy to do the impossible—save John Jay.

Almost before anything could get started, however, the students and faculty showed the spirit that would ultimately carry the day. On Thursday morning, February 26, three days after the announcement in the Times, a “Save John Jay” rally was held in front of South Hall. Even though it was bitterly cold, students and faculty filled 56th Street to listen to speeches about the emerging campaign. As the rally was breaking up, Netfa Fodiaba, president of the Student Council, spontaneously called on everyone to march on the Board of Higher Education headquarters at 80th Street and York Avenue. Thousands of students—police officers, firefighters, transit officers, and younger students—marched up the block to Ninth Avenue, turned north to 57th Street, and then headed east. Instead of the police stopping the demonstration, they cleared the way: they stopped traffic and allowed the march, which stretched three long blocks, to proceed unhindered.

The most remarkable aspect of the campaign to save John Jay was that all the elements that had given the college its unique qualities, but had often been “at war” with one another over the years, came together in a spirit of unity and common purpose. This esprit de corps surprised and invigorated everyone. Confronted with an outside threat, the college community closed ranks and was able to project its special qualities so that ordinary people were able to appreciate them. What caught people’s fancy was that this was a “college for cops,” but what convinced them of the importance of John Jay was that such a diverse faculty and student population could gather together, talk to one another, learn from one another, and become a community, united against dissolution.

The campaign succeeded. John Jay was saved.

1976 The college agrees to cut $2.3 million from the school’s budget (about 14.5%) in order to keep the school from being closed by CUNY.

1976 2,000 John Jay students rally in front of the school’s South Hall on 56th Street to protest the recommended closing of their college by CUNY. After holding the protest in front of the school, the group marches to the Board of Higher Education’s headquarters at 80th Street and York Ave. Students march there, shouting “SAVE JOHN JAY!”

1976 John Jay and Mayor Beame’s Midtown Enforcement Project receive a $17,000 federal grant to conduct a study of young prostitutes in Times Square.

1976 John Jay receives a $1.5 million grant from the U.S. Office of Education, titled “Toward Excellence in Criminal Justice Education: 1976-1979” to evaluate its undergraduate education program.

1977 Gerald Lynch, acting president of John Jay since 1975, is sworn in as college president, a position he held until 2004.

1977 Although John Jay avoided closing, the school is forced to narrow its focus to Criminal Justice and related fields. The following majors replace those in existence before May 4, 1977:

1977 John Jay receives a $350,000 grant from the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) to continue research into areas of police corruption. Data from a previous study had been used in national workshops in NYC, Boston, Atlanta and San Francisco.

1980 New York governor Hugh Carey approves the creation of a Ph.D. program in criminal justice, designed to begin at John Jay in the fall of 1981. It will be the second program of its kind in New York state and the first in the city.

1981 College courses are offered for the general public through John Jay College’s West Point Program. Courses include “The Legislative Process” and “War, Peace and Imperialism.”

1985 John Jay holds a celebratory event to commemorate its 20th anniversary with speeches, awards, and a reunion of those who helped found it.

1988 John Jay holds a dedication of its new building, Haaren Hall, on 10th Avenue and 59th Street. The $155 million renovation transformed the interior of the former Haaren High School, installing a new library, atrium, and classrooms.

1988 John Jay awards an honorary degree to Mother Teresa

In 1989, New York State was having another round of difficult fiscal times and had to make budget cuts and reduce state aid. CUNY undergraduates were probably going to see a $200 tuition increase. Incensed, John Jay students took over North Hall and Haaren Hall. The students were protesting not just because of budget cuts and tuition: they had an additional 24 demands they wanted met. Some demands included extending library hours, making athletic facilities available to evening students, and recruiting more faculty of color.

Negotiations were made and the students stopped protesting until a year later, when, in May 1990, students concluded that some of their concerns still had not been addressed. Protests began again outside the President’s office and students even put glue in the locks of many offices in North Hall. About 200 students took over North Hall and had a few scuffles with the police, which led to arrests and injuries. After three weeks and some canceled classes, the students finally released the building. Part of the agreement involved in ending the protest was to hold Town Hall meetings for faculty and students to come together and air with their concerns, which was a huge success.

In 1991, more takeovers were in store for the college: Latino students judged that their needs were not met in previous protests. This takeover was not as difficult as the previous protests had been, as the Town Hall meetings laid productive groundwork. The protests from 1989–91 led to distrust and uncertainty in John Jay, but also revealed the problems that needed to be worked out in order for John Jay students and faculty to come together as a community.

1989 Students from a number of CUNY schools, John Jay included, protest proposed budget cuts and tuition hikes by taking over administrative buildings at various schools. Gov. Cuomo refuses to meet with protesters over the proposed $200 increase as long as they continue to occupy school buildings

1990 Despite the end of takeovers at a number of other schools, John Jay students refuse to end their takeover of North Hall. Students cite a number of grievances against President Gerald Lynch, going so far as to call for his resignation. The tense situation is eventually defused, but not before 10 students are arrested during the protests.

1994 CUNY approves a new John Jay campus in Puerto Rico. In association with the Puerto Rican Police Academy, John Jay sends over 13 professors to develop a police science program.

1995 John Jay awards an honorary degree to Bill Cosby.

1998 John Jay receives $350 million in funds for a major building expansion. The New Building would open in 2011.

2001 John Jay loses 67 of its alumni during the World Trade Center attack. A number of them were police officers and firefighters.

Students on the Jay Walk

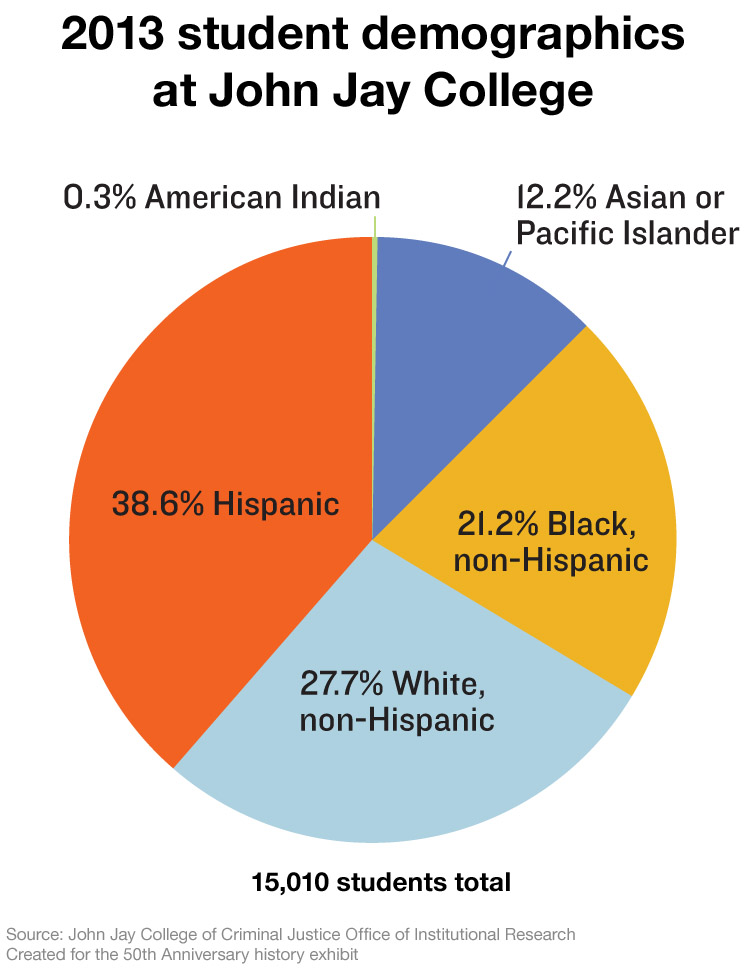

Students on the Jay WalkJohn Jay today is home to roughly 15,000 students in a diverse array of undergraduate, graduate and doctoral programs. Our student body produces leaders, scholars, and heroes in policing and beyond, including forensic science, law, fire and emergency management, social work, teaching, private security, forensic psychology and corrections. John Jay is also a leader in educating our nation’s military veterans, with more than 500 currently enrolled. The John Jay faculty, some 1,100 strong, includes Pulitzer Prize winners and widely honored scholars in a variety of academic fields.

Over the past 50 years, the College has expanded its educational focus to include a wide range of disciplines and professions, but the core mission of “educating for justice” remains inviolate and unchanged. The addition of many innovative liberal arts majors speaks to John Jay’s justice mission and reinforces the long-held view that the study of justice is intrinsically interdisciplinary. Now and always, we educate fierce advocates for justice.

2008 John Jay receives over $1.5 million in federal funds to support a number of research initiatives in Criminal Justice including gang violence, crime prevention, and domestic violence.

2008–2014 John Jay adopts a number of liberal arts majors including Gender Studies, Philosophy, History and Latino/Latina American Studies, as well as introducing several new minors, such as Sustainability and Environmental Justice.

2010 John Jay accepts its first ever all-Baccalaureate freshman class.

2011 John Jay opens the doors to its New Building facility, located on 59th Street between 10th and 11th Avenues.

2013 John Jay joins the Macaulay Honors Program, which awards promising students with full tuition for four years of undergraduate study and a research stipend.

2014 President Travis announces that the Campaign for the Future of Justice reaches its goal of $50 million for research grants, academic programming, and student scholarships

The essays in this exhibit were written by Brittany Cabanas, Jakub Gaweda, and Kayla

Talbot

with help from Jerry Markowitz, Fritz Umbach, and Robin Davis.

Images and text from this exhibit are also on display in Haaren Hall.

Curated by Claudia Calirman, Robin Davis, Jerry Markowitz, Ellen Sexton, and Fritz Umbach, with the help of Brittany Cabanas, Jakub Gaweda, and Kayla Talbot. Special thanks to Dean of Undergraduate Studies Allison Pease, Bill Pangburn, Jeff Brown, Vice President Jayne Rosengarten, and the Lloyd Sealy Library.

Text and information in this exhibit is taken from Educating for Justice: a History of John Jay College by Gerald (Jerry) E. Markowitz, published 2008 [c2004] by John Jay Press and available in the John Jay Library.